11.1 Principles of Biotechnology

11.2 Tools of Recombinant DNA

Technology

11.3 Processes of Recombinant

DNA Technology

Biotechnology deals with techniques of using live

organisms or enzymes from organisms to produce products

and processes useful to humans. In this sense, making

curd, bread or wine, which are all microbe-mediated

processes, could also be thought as a form of

biotechnology. However, it is used in a restricted sense

today, to refer to such of those processes which use

genetically modified organisms to achieve the same on a

larger scale. Further, many other processes/techniques are

also included under biotechnology. For example, in vitro

fertilisation leading to a ‘test-tube’ baby, synthesising a

gene and using it, developing a DNA vaccine or correcting

a defective gene, are all part of biotechnology.

The European Federation of Biotechnology (EFB) has

given a definition of biotechnology that encompasses both

traditional view and modern molecular biotechnology.

The definition given by EFB is as follows:

‘The integration of natural science and organisms,

cells, parts thereof, and molecular analogues for products

and services’.

11.1 PRINCIPLES OF BIOTECHNOLOGY

Among many, the two core techniques that enabled birth

of modern biotechnology are :

(i) Genetic engineering : Techniques to alter the

chemistry of genetic material (DNA and RNA),

to introduce these into host organisms and thus change the

phenotype of the host organism.

(ii) Bioprocess engineering: Maintenance of sterile (microbial

contamination-free) ambience in chemical engineering processes

to enable growth of only the desired microbe/eukaryotic cell in

large quantities for the manufacture of biotechnological products

like antibiotics, vaccines, enzymes, etc.

Let us now understand the conceptual development of the principles

of genetic engineering.

You probably appreciate the advantages of sexual reproduction over

asexual reproduction. The former provides opportunities for variations

and formulation of unique combinations of genetic setup, some of which

may be beneficial to the organism as well as the population. Asexual

reproduction preserves the genetic information, while sexual reproduction

permits variation. Traditional hybridisation procedures used in plant and

animal breeding, very often lead to inclusion and multiplication of

undesirable genes along with the desired genes. The techniques of genetic

engineering which include creation of recombinant DNA, use of

gene cloning and gene transfer, overcome this limitation and allows us

to isolate and introduce only one or a set of desirable genes without

introducing undesirable genes into the target organism.

Do you know the likely fate of a piece of DNA, which is somehow

transferred into an alien organism? Most likely, this piece of DNA would

not be able to multiply itself in the progeny cells of the organism. But,

when it gets integrated into the genome of the recipient, it may multiply

and be inherited along with the host DNA. This is because the alien piece

of DNA has become part of a chromosome, which has the ability to

replicate. In a chromosome there is a specific DNA sequence called the

origin of replication, which is responsible for initiating replication.

Therefore, for the multiplication of any alien piece of DNA in an organism

it needs to be a part of a chromosome(s) which has a specific sequence

known as ‘origin of replication’. Thus, an alien DNA is linked with the

origin of replication, so that, this alien piece of DNA can replicate and

multiply itself in the host organism. This can also be called as cloning or

making multiple identical copies of any template DNA.

Let us now focus on the first instance of the construction of an artificial

recombinant DNA molecule. The construction of the first recombinant

DNA emerged from the possibility of linking a gene encoding antibiotic

resistance with a native plasmid (autonomously replicating circular

extra-chromosomal DNA) of Salmonella typhimurium. Stanley Cohen and

Herbert Boyer accomplished this in 1972 by isolating the antibiotic

resistance gene by cutting out a piece of DNA from a plasmid which was

responsible for conferring antibiotic resistance. The cutting of DNA at

specific locations became possible with the discovery of the so-called

‘molecular scissors’– restriction enzymes. The cut piece of DNA was

then linked with the plasmid DNA. These plasmid DNA act as vectors to

transfer the piece of DNA attached to it. You probably know that mosquito

acts as an insect vector to transfer the malarial parasite into human body.

In the same way, a plasmid can be used as vector to deliver an alien piece

of DNA into the host organism. The linking of antibiotic resistance gene

with the plasmid vector became possible with the enzyme DNA ligase,

which acts on cut DNA molecules and joins their ends. This makes a new

combination of circular autonomously replicating DNA created in vitro

and is known as recombinant DNA. When this DNA is transferred into

Escherichia coli, a bacterium closely related to Salmonella, it could

replicate using the new host’s DNA polymerase enzyme and make multiple

copies. The ability to multiply copies of antibiotic resistance gene in

E. coli was called cloning of antibiotic resistance gene in E. coli.

You can hence infer that there are three basic steps in genetically

modifying an organism —

(i) identification of DNA with desirable genes;

(ii) introduction of the identified DNA into the host;

(iii) maintenance of introduced DNA in the host and transfer of the DNA

to its progeny.

11.2 TOOLS OF RECOMBINANT DNA TECHNOLOGY

Now we know from the foregoing discussion that genetic engineering or

recombinant DNA technology can be accomplished only if we have the

key tools, i.e., restriction enzymes, polymerase enzymes, ligases, vectors

and the host organism. Let us try to understand some of these in detail.

11.2.1 Restriction Enzymes

In the year 1963, the two enzymes responsible for restricting the growth

of bacteriophage in Escherichia coli were isolated. One of these added

methyl groups to DNA, while the other cut DNA. The later was called

restriction endonuclease.

The first restriction endonuclease–Hind II, whose functioning

depended on a specific DNA nucleotide sequence was isolated and

characterised five years later. It was found that Hind II always cut DNA

molecules at a particular point by recognising a specific sequence of

six base pairs. This specific base sequence is known as the

recognition sequence for Hind II. Besides Hind II, today we know more

than 900 restriction enzymes that have been isolated from over 230 strains

of bacteria each of which recognise different recognition sequences.

The convention for naming these enzymes is the first letter of the name

comes from the genus and the second two letters come from the species of

the prokaryotic cell from which they were isolated, e.g., EcoRI comes from

Escherichia coli RY 13. In EcoRI, the letter ‘R’ is derived from the name of

strain. Roman numbers following the names indicate the order in which

the enzymes were isolated from that strain of bacteria.

Restriction enzymes belong to a larger class of enzymes called

nucleases. These are of two kinds; exonucleases and endonucleases.

Exonucleases remove nucleotides from the ends of the DNA whereas,

endonucleases make cuts at specific positions within the DNA.

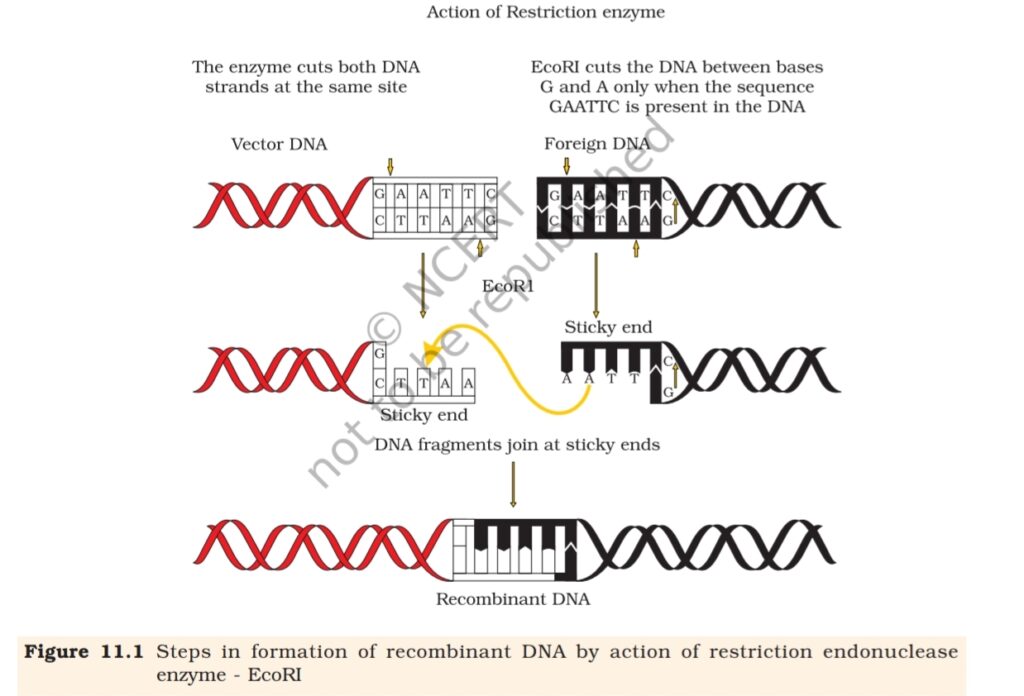

Each restriction endonuclease functions by ‘inspecting’ the length of

a DNA sequence. Once it finds its specific recognition sequence, it

will bind to the DNA and cut each of the two strands of the double

helix at specific points in their sugar -phosphate backbones

(Figure 11.1). Each restriction endonuclease recognises a specific

palindromic nucleotide sequences in the DNA.

Do you know what palindromes are? These are groups of letters

that form the same words when read both forward and backward,

e.g., “MALAYALAM”. As against a word-palindrome where the same

word is read in both directions, the palindrome in DNA is a sequence

of base pairs that reads same on the two strands when orientation of

reading is kept the same. For example, the following sequences reads

the same on the two strands in 5′ à 3′ direction. This is also true if

read in the 3′ à 5′ direction.

5′ —— GAATTC —— 3′

3′ —— CTTAAG —— 5′

Restriction enzymes cut the strand of DNA a little away from the centre

of the palindrome sites, but between the same two bases on the opposite

strands. This leaves single stranded portions at the ends. There are

overhanging stretches called sticky ends on each strand (Figure 11.1).

These are named so because they form hydrogen bonds with their

complementary cut counterparts. This stickiness of the ends facilitates

the action of the enzyme DNA ligase.

Restriction endonucleases are used in genetic engineering to form

‘recombinant’ molecules of DNA, which are composed of DNA from

different sources/genomes.

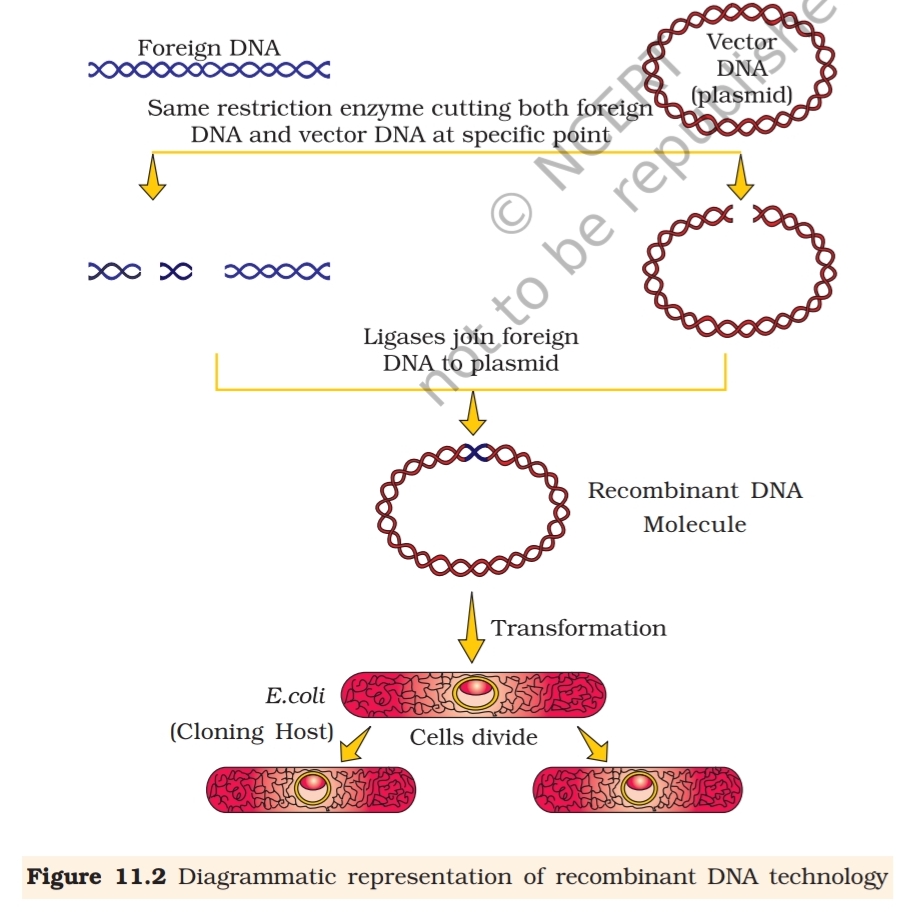

When cut by the same restriction enzyme, the resultant DNA fragments

have the same kind of ‘sticky-ends’ and, these can be joined together

(end-to-end) using DNA ligases (Figure 11.2).

You may have realised that normally, unless one cuts the vector and

the source DNA with the same restriction enzyme, the recombinant vector

molecule cannot be created.

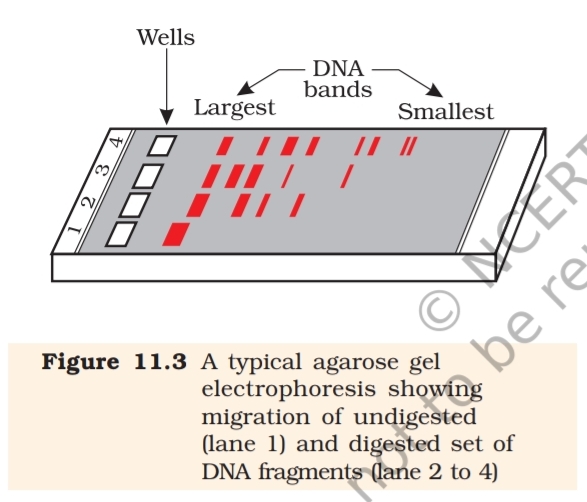

Separation and isolation of DNA fragments : The cutting of DNA by

restriction endonucleases results in the fragments of DNA. These fragments

can be separated by a technique known as gel electrophoresis. Since

DNA fragments are negatively charged molecules they can be separated

by forcing them to move towards the anode under an electric field through

a medium/matrix. Nowadays the most commonly used matrix is agarose

which is a natural polymer extracted from sea weeds. The DNA fragments

separate (resolve) according to their size through sieving effect provided

by the agarose gel. Hence, the smaller the fragment size, the farther it

moves. Look at the Figure 11.3 and guess at which end of the gel the

sample was loaded.

You may have realised that normally, unless one cuts the vector and

the source DNA with the same restriction enzyme, the recombinant vector

molecule cannot be created.

Separation and isolation of DNA fragments : The cutting of DNA by

restriction endonucleases results in the fragments of DNA. These fragments

can be separated by a technique known as gel electrophoresis. Since

DNA fragments are negatively charged molecules they can be separated

by forcing them to move towards the anode under an electric field through

a medium/matrix. Nowadays the most commonly used matrix is agarose

which is a natural polymer extracted from sea weeds. The DNA fragments

separate (resolve) according to their size through sieving effect provided

by the agarose gel. Hence, the smaller the fragment size, the farther it

moves. Look at the Figure 11.3 and guess at which end of the gel the

sample was loaded.

The separated DNA fragments can be

visualised only after staining the DNA

with a compound known as ethidium

bromide followed by exposure to UV

radiation (you cannot see pure DNA

fragments in the visible light and

without staining). You can see bright

orange coloured bands of DNA in a

ethidium bromide stained gel

exposed to UV light (Figure 11.3). The

separated bands of DNA are cut out

from the agarose gel and extracted

from the gel piece. This step is known

as elution. The DNA fragments

purified in this way are used in

constructing recombinant DNA by

joining them with cloning vectors.

11.2.2 Cloning Vectors

You know that plasmids and bacteriophages have the ability to replicate

within bacterial cells independent of the control of chromosomal DNA.

Bacteriophages because of their high number per cell, have very high

copy numbers of their genome within the bacterial cells. Some plasmids

may have only one or two copies per cell whereas others may have

15-100 copies per cell. Their numbers can go even higher. If we are able

to link an alien piece of DNA with bacteriophage or plasmid DNA, we can

multiply its numbers equal to the copy number of the plasmid or

bacteriophage. Vectors used at present, are engineered in such a way

that they help easy linking of foreign DNA and selection of recombinants

from non-recombinants.

The following are the features that are required to facilitate cloning

into a vector.

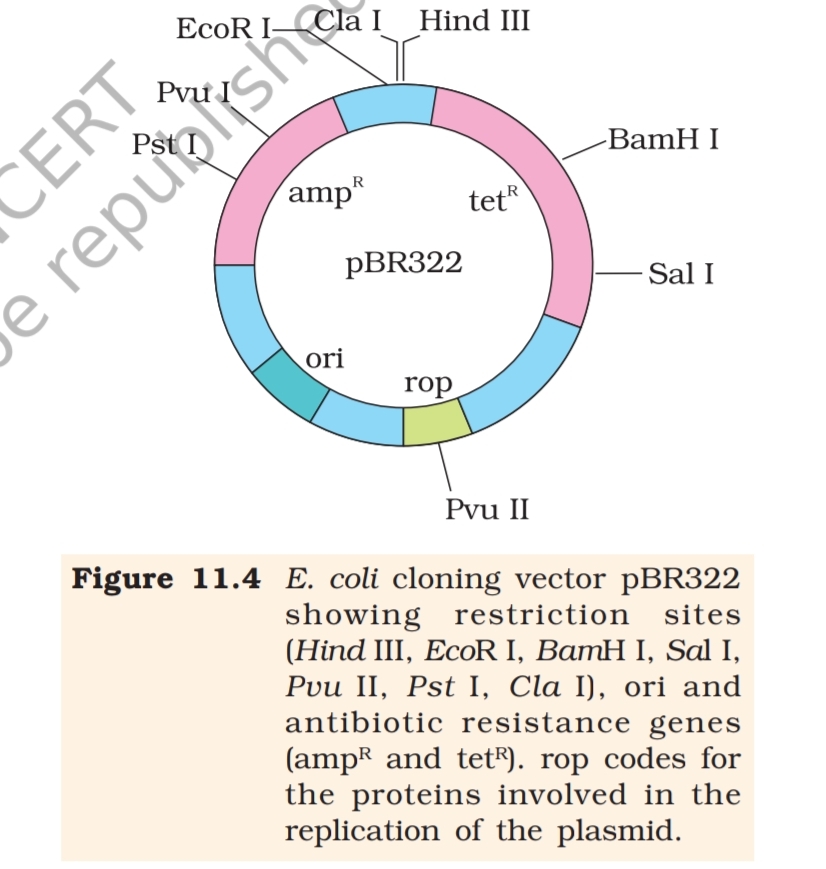

(i) Origin of replication (ori) : This is a sequence from where

replication starts and any piece of DNA when linked to this sequence

can be made to replicate within the host cells. This sequence is also

responsible for controlling the copy number of the linked DNA. So,

if one wants to recover many copies of the target DNA it should be

cloned in a vector whose origin support high copy number.

(ii) Selectable marker : In addition to ‘ori’, the vector requires a

selectable marker, which helps in identifying and eliminating non-

transformants and selectively permitting the growth of the

transformants. Transformation is a procedure through which a

piece of DNA is introduced in a host bacterium (you will study the

process in subsequent section). Normally, the genes encoding

resistance to antibiotics such as ampicillin, chloramphenicol,

tetracycline or kanamycin, etc., are considered useful selectable

markers for E. coli. The normal E. coli cells do not carry resistance

against any of these antibiotics.

(iii) Cloning sites: In order to link the

alien DNA, the vector needs to have

very few, preferably single,

recognition sites for the commonly

used restriction enzymes. Presence of

more than one recognition sites within

the vector will generate several

fragments, which will complicate the

gene cloning (Figure 11.4). The

ligation of alien DNA is carried out at

a restriction site present in one of the

two antibiotic resistance genes. For

example, you can ligate a foreign DNA

at the BamH I site of tetracycline

resistance gene in the vector pBR322.

The recombinant plasmids will lose

tetracycline resistance due to insertion

of foreign DNA but can still be selected

out from non-recombinant ones by

plating the transformants on

tetracycline containing medium. The transformants growing on

ampicillin containing medium are then transferred on a medium

containing tetracycline. The recombinants will grow in ampicillin

containing medium but not on that containing tetracycline. But,

non- recombinants will grow on the medium containing both the

antibiotics. In this case, one antibiotic resistance gene helps in

selecting the transformants, whereas the other antibiotic resistance

gene gets ‘inactivated due to insertion’ of alien DNA, and helps in

selection of recombinants.

Selection of recombinants due to inactivation of antibiotics is a

cumbersome procedure because it requires simultaneous plating

on two plates having different antibiotics. Therefore, alternative

selectable markers have been developed which differentiate

recombinants from non-recombinants on the basis of their ability

to produce colour in the presence of a chromogenic substrate. In

this, a recombinant DNA is inserted within the coding sequence of

an enzyme, β-galactosidase. This results into inactivation of the

gene for synthesis of this enzyme, which is referred to as insertional

inactivation. The presence of a chromogenic substrate gives blue

coloured colonies if the plasmid in the bacteria does not have an

insert. Presence of insert results into insertional inactivation of the

β-galactosidase gene and the colonies do not produce any colour,

these are identified as recombinant colonies.

(iv) Vectors for cloning genes in plants and animals : You may be

surprised to know that we have learnt the lesson of transferring genes

into plants and animals from bacteria and viruses which have known

this for ages – how to deliver genes to transform eukaryotic cells and

force them to do what the bacteria or viruses want. For example,

Agrobacterium tumifaciens, a pathogen of several dicot plants is able

to deliver a piece of DNA known as ‘T-DNA’ to transform normal

plant cells into a tumor and direct these tumor cells to produce the

chemicals required by the pathogen. Similarly, retroviruses in animals

have the ability to transform normal cells into cancerous cells. A

better understanding of the art of delivering genes by pathogens in

their eukaryotic hosts has generated knowledge to transform these

tools of pathogens into useful vectors for delivering genes of interest

to humans. The tumor inducing (Ti) plasmid of Agrobacterium

tumifaciens has now been modified into a cloning vector which is no

more pathogenic to the plants but is still able to use the mechanisms

to deliver genes of our interest into a variety of plants. Similarly,

retroviruses have also been disarmed and are now used to deliver

desirable genes into animal cells. So, once a gene or a DNA fragment

has been ligated into a suitable vector it is transferred into a bacterial,

plant or animal host (where it multiplies).

11.2.3 Competent Host (For Transformation with

Recombinant DNA)

Since DNA is a hydrophilic molecule, it cannot pass through cell

membranes. Why? In order to force bacteria to take up the plasmid, the

bacterial cells must first be made ‘competent’ to take up DNA. This is

done by treating them with a specific concentration of a divalent cation,

such as calcium, which increases the efficiency with which DNA enters

the bacterium through pores in its cell wall. Recombinant DNA can then

be forced into such cells by incubating the cells with recombinant DNA

on ice, followed by placing them briefly at 420C (heat shock), and then

putting them back on ice. This enables the bacteria to take up the

recombinant DNA.

This is not the only way to introduce alien DNA into host cells. In a

method known as micro-injection, recombinant DNA is directly injected

into the nucleus of an animal cell. In another method, suitable for plants,

cells are bombarded with high velocity micro-particles of gold or tungsten

coated with DNA in a method known as biolistics or gene gun. And the

last method uses ‘disarmed pathogen’ vectors, which when allowed to

infect the cell, transfer the recombinant DNA into the host.

Now that we have learnt about the tools for constructing recombinant

DNA, let us discuss the processes facilitating recombinant DNA technology.

11.3 PROCESSES OF RECOMBINANT DNA TECHNOLOGY

Recombinant DNA technology involves several steps in specific

sequence such as isolation of DNA, fragmentation of DNA by

restriction endonucleases, isolation of a desired DNA fragment,

ligation of the DNA fragment into a vector, transferring the

recombinant DNA into the host, culturing the host cells in a

medium at large scale and extraction of the desired product.

Let us examine each of these steps in some details.

11.3.1 Isolation of the Genetic Material (DNA)

Recall that nucleic acid is the genetic material of all organisms

without exception. In majority of organisms this is

deoxyribonucleic acid or DNA. In order to cut the DNA with

restriction enzymes, it needs to be in pure form, free from other

macro-molecules. Since the DNA is enclosed within the

membranes, we have to break the cell open to release DNA along

with other macromolecules such as RNA, proteins,

polysaccharides and also lipids. This can be achieved by treating

the bacterial cells/plant or animal tissue with enzymes such as

lysozyme (bacteria), cellulase (plant cells), chitinase (fungus).

You know that genes are located on long molecules of DNA

interwined with proteins such as histones. The RNA can be removed by

treatment with ribonuclease whereas proteins can be removed by

treatment with protease. Other molecules can be removed by appropriate

treatments and purified DNA ultimately precipitates out after the addition

of chilled ethanol. This can be seen as collection of fine threads in the

suspension (Figure 11.5).

11.3.2 Cutting of DNA at Specific Locations

Restriction enzyme digestions are performed by incubating purified DNA

molecules with the restriction enzyme, at the optimal conditions for that

specific enzyme. Agarose gel electrophoresis is employed to check the

progression of a restriction enzyme digestion. DNA is a negatively charged

molecule, hence it moves towards the positive electrode (anode)

(Figure 11.3). The process is repeated with the vector DNA also.

The joining of DNA involves several processes. After having cut the

source DNA as well as the vector DNA with a specific restriction enzyme,

the cut out ‘gene of interest’ from the source DNA and the cut vector with

space are mixed and ligase is added. This results in the preparation of

recombinant DNA.

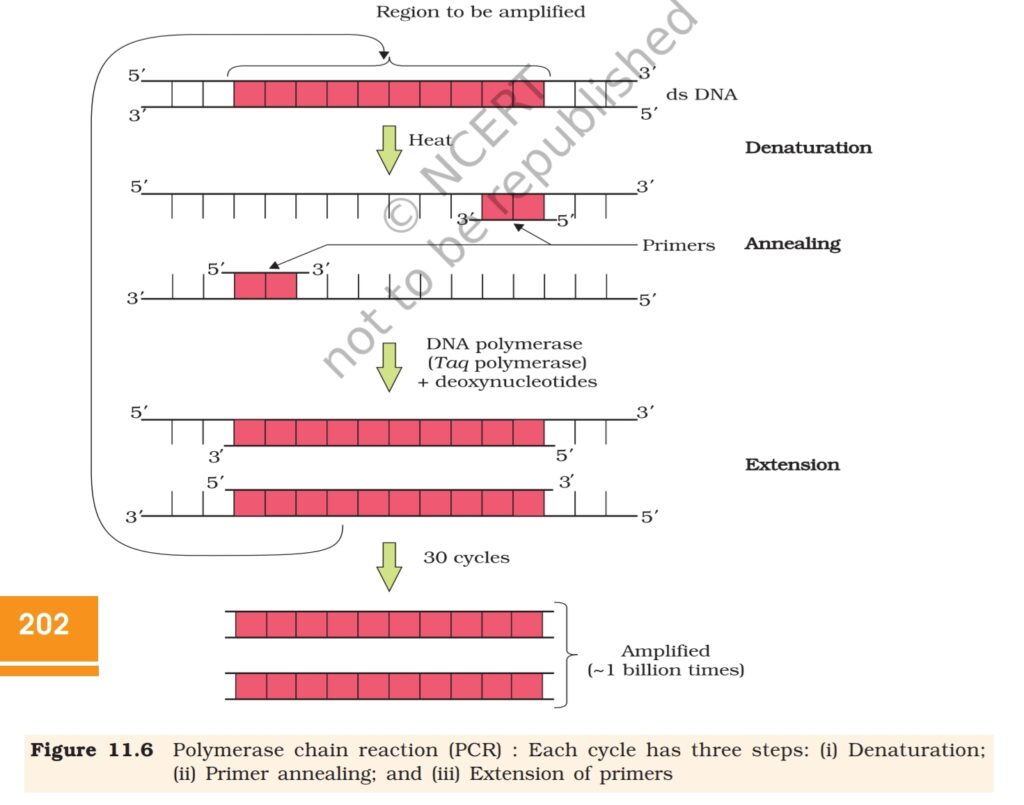

11.3.3 Amplification of Gene of Interest using PCR

PCR stands for Polymerase Chain Reaction. In this reaction, multiple

copies of the gene (or DNA) of interest is synthesised in vitro using two

sets of primers (small chemically synthesised oligonucleotides that are

complementary to the regions of DNA) and the enzyme DNA polymerase.

The enzyme extends the primers using the nucleotides provided in the

reaction and the genomic DNA as template. If the process of replication

of DNA is repeated many times, the segment of DNA can be amplified

to approximately billion times, i.e., 1 billion copies are made. Such

repeated amplification is achieved by the use of a thermostable DNA

polymerase (isolated from a bacterium, Thermus aquaticus), which

remain active during the high temperature induced denaturation of

double stranded DNA. The amplified fragment if desired can now be

used to ligate with a vector for further cloning (Figure11.6).

11.3.4 Insertion of Recombinant DNA into the Host

Cell/Organism

There are several methods of introducing the ligated DNA into recipient

cells. Recipient cells after making them ‘competent’ to receive, take up

DNA present in its surrounding. So, if a recombinant DNA bearing gene

for resistance to an antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin) is transferred into E. coli

cells, the host cells become transformed into ampicillin-resistant cells. If

we spread the transformed cells on agar plates containing ampicillin, only

transformants will grow, untransformed recipient cells will die. Since, due

to ampicillin resistance gene, one is able to select a transformed cell in the

presence of ampicillin. The ampicillin resistance gene in this case is called

a selectable marker.

11.3.5 Obtaining the Foreign Gene Product

When you insert a piece of alien DNA into a cloning vector and transfer it

into a bacterial, plant or animal cell, the alien DNA gets multiplied. In

almost all recombinant technologies, the ultimate aim is to produce a

desirable protein. Hence, there is a need for the recombinant DNA to be

expressed. The foreign gene gets expressed under appropriate conditions.

The expression of foreign genes in host cells involve understanding many

technical details.

After having cloned the gene of interest and having optimised the

conditions to induce the expression of the target protein, one has to

consider producing it on a large scale. Can you think of any reason

why there is a need for large-scale production? If any protein encoding

gene is expressed in a heterologous host, it is called a recombinant

protein. The cells harbouring cloned genes of interest may be grown

on a small scale in the laboratory. The cultures may be used for

extracting the desired protein and then purifying it by using different

separation techniques.

The cells can also be multiplied in a continuous culture system wherein

the used medium is drained out from one side while fresh medium is

added from the other to maintain the cells in their physiologically most

active log/exponential phase. This type of culturing method produces a

larger biomass leading to higher yields of desired protein.

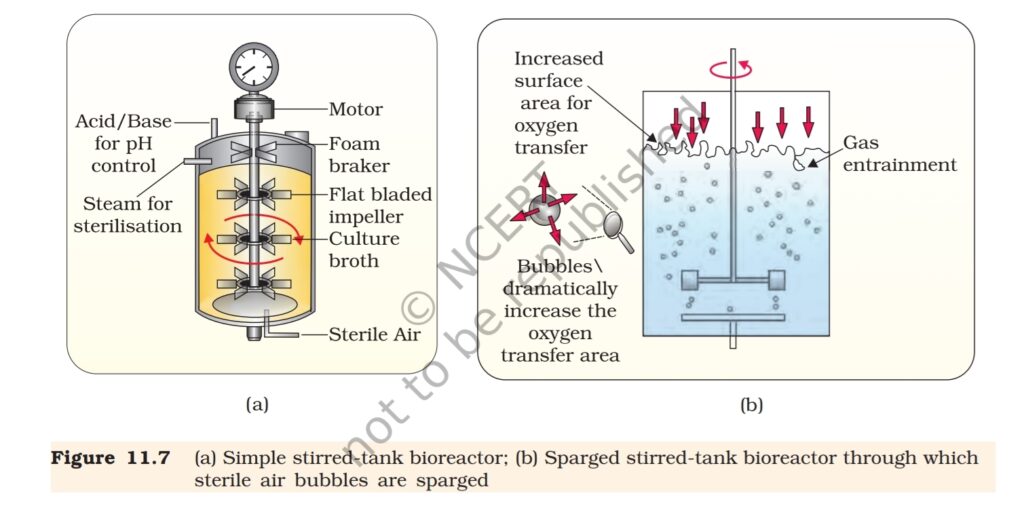

Small volume cultures cannot yield appreciable quantities of products.

To produce in large quantities, the development of bioreactors, where

large volumes (100-1000 litres) of culture can be processed, was required.

Thus, bioreactors can be thought of as vessels in which raw materials are

biologically converted into specific products, individual enzymes, etc.,

using microbial plant, animal or human cells. A bioreactor provides the

optimal conditions for achieving the desired product by providing

optimum growth conditions (temperature, pH, substrate, salts, vitamins,

oxygen).

The most commonly used bioreactors are of stirring type, which are

shown in Figure 11.7.

A stirred-tank reactor is usually cylindrical or with a curved base to

facilitate the mixing of the reactor contents. The stirrer facilitates even

mixing and oxygen availability throughout the bioreactor. Alternatively

air can be bubbled through the reactor. If you look at the figure closely

you will see that the bioreactor has an agitator system, an oxygen delivery

system and a foam control system, a temperature control system, pH

control system and sampling ports so that small volumes of the culture

can be withdrawn periodically.

11.3.6 Downstream Processing

After completion of the biosynthetic stage, the product has to be subjected

through a series of processes before it is ready for marketing as a finished

product. The processes include separation and purification, which are

collectively referred to as downstream processing. The product has to be

formulated with suitable preservatives. Such formulation has to undergo

thorough clinical trials as in case of drugs. Strict quality control testing

for each product is also required. The downstream processing and quality

control testing vary from product to product.

SUMMARY

Biotechnology deals with large scale production and marketing of

products and processes using live organisms, cells or enzymes.

Modern biotechnology using genetically modified organisms was

made possible only when man learnt to alter the chemistry of DNA

and construct recombinant DNA. This key process is called

recombinant DNA technology or genetic engineering. This process

involves the use of restriction endonucleases, DNA ligase,

appropriate plasmid or viral vectors to isolate and ferry the foreign

DNA into host organisms, expression of the foreign gene, purification

of the gene product, i.e., the functional protein and finally making a

suitable formulation for marketing. Large scale production involves

use of bioreactors.

EXERCISES

- Can you list 10 recombinant proteins which are used in medical

practice? Find out where they are used as therapeutics (use the internet). - Make a chart (with diagrammatic representation) showing a restriction

enzyme, the substrate DNA on which it acts, the site at which it cuts

DNA and the product it produces. - From what you have learnt, can you tell whether enzymes are bigger or

DNA is bigger in molecular size? How did you know? - What would be the molar concentration of human DNA in a human

cell? Consult your teacher. - Do eukaryotic cells have restriction endonucleases? Justify your answer.

- Besides better aeration and mixing properties, what other advantages

do stirred tank bioreactors have over shake flasks? - Collect 5 examples of palindromic DNA sequences by consulting your teacher.

Better try to create a palindromic sequence by following base-pair rules. - Can you recall meiosis and indicate at what stage a recombinant DNA

is made? - Can you think and answer how a reporter enzyme can be used to monitor

transformation of host cells by foreign DNA in addition to a selectable

marker?

- Describe briefly the following:

(a) Origin of replication

(b) Bioreactors

(c) Downstream processing - Explain briefly

(a) PCR

(b) Restriction enzymes and DNA

(c) Chitinase - Discuss with your teacher and find out how to distinguish between

(a) Plasmid DNA and Chromosomal DNA

(b) RNA and DNA

(c) Exonuclease and Endonuclease

One response to “CHAPTER 11 BIOTECHNOLOGY : PRINCIPLESAND PROCESSES”

This was exactly what I was looking for.