15.1 Biodiversity

15.2 Biodiversity Conservation

If an alien from a distant galaxy were to visit our planet

Earth, the first thing that would amaze and baffle him

would most probably be the enormous diversity of life

that he would encounter. Even for humans, the rich variety

of living organisms with which they share this planet never

ceases to astonish and fascinate us. The common man

would find it hard to believe that there are more than

20,000 species of ants, 3,00,000 species of beetles, 28,000

species of fishes and nearly 20,000 species of orchids.

Ecologists and evolutionary biologists have been trying

to understand the significance of such diversity by asking

important questions– Why are there so many species?

Did such great diversity exist throughout earth’s history?

How did this diversification come about? How and why

is this diversity important to the biosphere? Would it

function any differently if the diversity was much less?

How do humans benefit from the diversity of life?

15.1 BIODIVERSITY

In our biosphere immense diversity (or heterogeneity)

exists not only at the species level but at all levels of

biological organisation ranging from macromolecules

within cells to biomes. Biodiversity is the term popularised

by the sociobiologist Edward Wilson to describe the

combined diversity at all the levels of biological organisation.

The most important of them are–

(i) Genetic diversity: A single species might show high diversity at

the genetic level over its distributional range. The genetic variation

shown by the medicinal plant Rauwolfia vomitoria growing in

different Himalayan ranges might be in terms of the potency and

concentration of the active chemical (reserpine) that the plant

produces. India has more than 50,000 genetically different strains

of rice, and 1,000 varieties of mango.

(ii) Species diversity: The diversity at the species level, for example,

the Western Ghats have a greater amphibian species diversity than

the Eastern Ghats.

(iii) Ecological diversity: At the ecosystem level, India, for instance,

with its deserts, rain forests, mangroves, coral reefs, wetlands,

estuaries, and alpine meadows has a greater ecosystem diversity

than a Scandinavian country like Norway.

It has taken millions of years of evolution, to accumulate this rich

diversity in nature, but we could lose all that wealth in less than two

centuries if the present rates of species losses continue. Biodiversity and

its conservation are now vital environmental issues of international concern

as more and more people around the world begin to realise the critical

importance of biodiversity for our survival and well- being on this planet.

15.1.1 How Many Species are there on Earth and How

Many in India?

Since there are published records of all the species discovered and named,

we know how many species in all have been recorded so far, but it is not

easy to answer the question of how many species there are on earth.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and

Natural Resources (IUCN) (2004), the total number of plant and animal

species described so far is slightly more than 1.5 million, but we have no

clear idea of how many species are yet to be discovered and described.

Estimates vary widely and many of them are only educated guesses. For

many taxonomic groups, species inventories are more complete in

temperate than in tropical countries. Considering that an overwhelmingly

large proportion of the species waiting to be discovered are in the tropics,

biologists make a statistical comparison of the temperate-tropical species

richness of an exhaustively studied group of insects and extrapolate this

ratio to other groups of animals and plants to come up with a gross

estimate of the total number of species on earth. Some extreme estimates

range from 20 to 50 million, but a more conservative and scientifically

sound estimate made by Robert May places the global species diversity

at about 7 million.

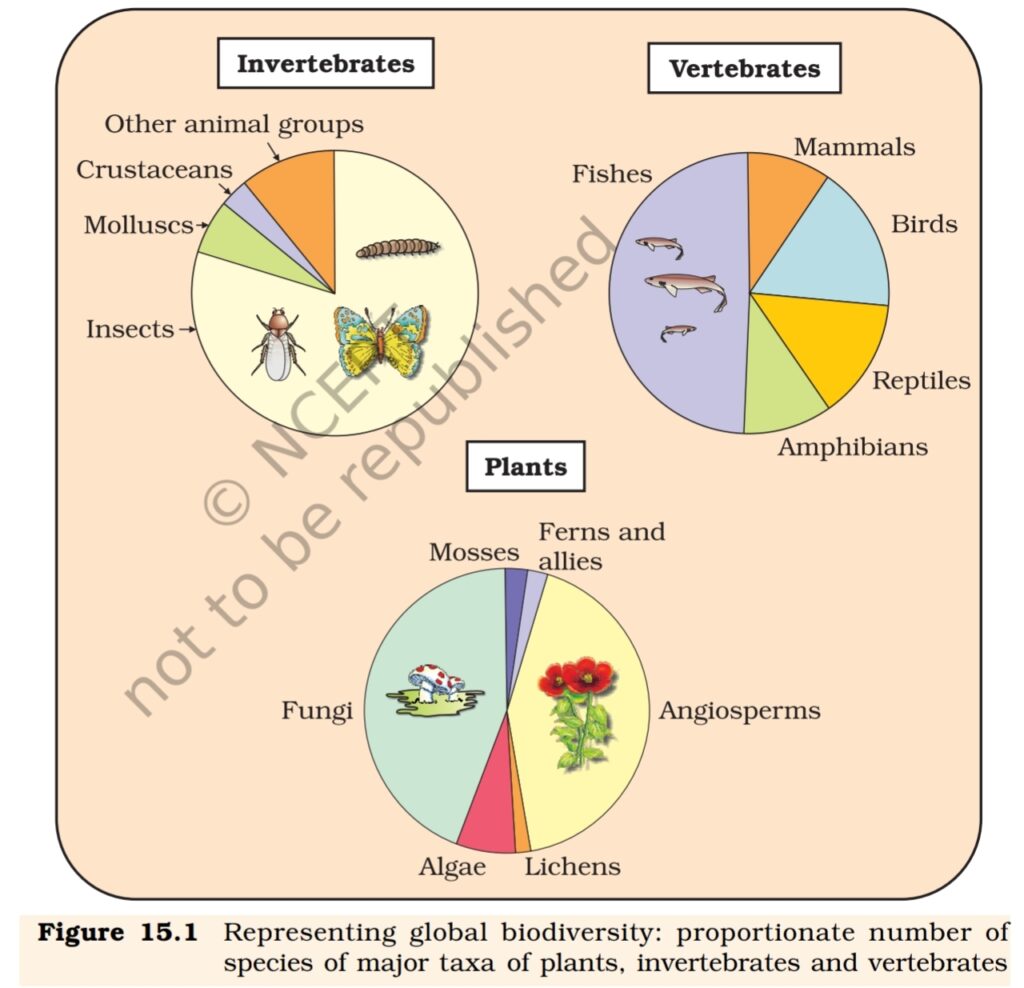

Let us look at some interesting aspects about earth’s biodiversity based

on the currently available species inventories. More than 70 per cent of

all the species recorded are animals, while plants (including algae, fungi,

bryophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms) comprise no more than 22

per cent of the total. Among animals, insects are the most species-rich

taxonomic group, making up more than 70 per cent of the total. That

means, out of every 10 animals on this planet, 7 are insects. Again, how

do we explain this enormous diversification of insects? The number of

fungi species in the world is more than the combined total of the species

of fishes, amphibians, reptiles and mammals. In Figure 15.1, biodiversity

is depicted showing species number of major taxa.

It should be noted that these estimates do not give any figures for

prokaryotes. Biologists are not sure about how many prokaryotic species

there might be. The problem is that conventional taxonomic methods are

not suitable for identifying microbial species and many species are simply

not culturable under laboratory conditions. If we accept biochemical or

molecular criteria for delineating species for this group, then their diversity

alone might run into millions.

Although India has only 2.4 per cent of the world’s land area, its share

of the global species diversity is an impressive 8.1 per cent. That is what

makes our country one of the 12 mega diversity countries of the world.

Nearly 45,000 species of plants and twice as many of animals have been

recorded from India. How many living species are actually there waiting

to be discovered and named? If we accept May’s global estimates, only

22 per cent of the total species have been recorded so far. Applying this

proportion to India’s diversity figures, we estimate that there are probably

more than 1,00,000 plant species and more than 3,00,000 animal species

yet to be discovered and described. Would we ever be able to complete

the inventory of the biological wealth of our country? Consider the immense

trained manpower (taxonomists) and the time required to complete the

job. The situation appears more hopeless when we realise that a large

fraction of these species faces the threat of becoming extinct even before

we discover them. Nature’s biological library is burning even before we

catalogued the titles of all the books stocked there.

15.1.2 Patterns of Biodiversity

(i) Latitudinal gradients : The diversity of plants and animals is

not uniform throughout the world but shows a rather uneven

distribution. For many group of animals or plants, there are

interesting patterns in diversity, the most well- known being the

latitudinal gradient in diversity. In general, species diversity

decreases as we move away from the equator towards the poles.

With very few exceptions, tropics (latitudinal range of 23.5° N to

23.5° S) harbour more species than temperate or polar areas.

Colombia located near the equator has nearly 1,400 species of birds

while New York at 41° N has 105 species and Greenland at 71° N

only 56 species. India, with much of its land area in the tropical

latitudes, has more than 1,200 species of birds. A forest in a tropical

region like Equador has up to 10 times as many species of vascular

plants as a forest of equal area in a temperate region like the Midwest

of the USA. The largely tropical Amazonian rain forest in South

America has the greatest biodiversity on earth- it is home to more

than 40,000 species of plants, 3,000 of fishes, 1,300 of birds, 427

of mammals, 427 of amphibians, 378 of reptiles and of more than

1,25,000 invertebrates. Scientists estimate that in these rain forests

there might be at least two million insect species waiting to be

discovered and named.

What is so special about tropics that might account for their greater

biological diversity? Ecologists and evolutionary biologists have

proposed various hypotheses; some important ones are (a) Speciation

is generally a function of time, unlike temperate regions subjected

to frequent glaciations in the past, tropical latitudes have remained

relatively undisturbed for millions of years and thus, had a long

evolutionary time for species diversification, (b) Tropical environments,

unlike temperate ones, are less seasonal, relatively more constant

and predictable. Such constant environments promote niche

specialisation and lead to a greater species diversity and (c) There

is more solar energy available in the tropics, which contributes to

higher productivity; this in turn might contribute indirectly to greater

diversity.

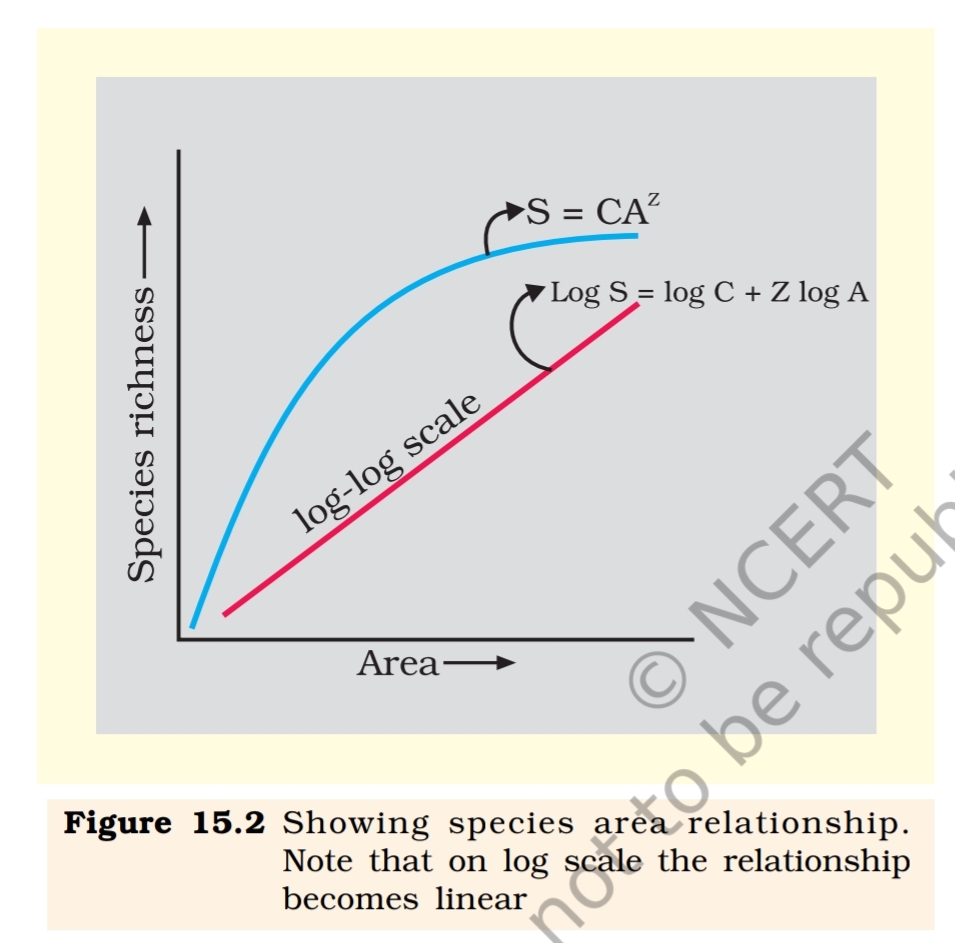

(ii) Species-Area relationships: During his pioneering and extensive

explorations in the wilderness of South American jungles, the great

German naturalist and geographer Alexander von Humboldt

observed that within a region species

richness increased with increasing

explored area, but only up to a limit. In

fact, the relation between species richness

and area for a wide variety of taxa

(angiosperm plants, birds, bats,

freshwater fishes) turns out to be a

rectangular hyperbola (Figure15.2). On

a logarithmic scale, the relationship is a

straight line described by the equation

log S = log C + Z log A

where

S= Species richness A= Area

Z = slope of the line (regression

coefficient)

C = Y-intercept

Ecologists have discovered that the

value of Z lies in the range of 0.1 to 0.2,

regardless of the taxonomic group or the

region (whether it is the plants in Britain,

birds in California or molluscs in New York state, the slopes of the regression

line are amazingly similar). But, if you analyse the species-area

relationships among very large areas like the entire continents, you will

find that the slope of the line to be much steeper (Z values in the range

of 0.6 to 1.2). For example, for frugivorous (fruit-eating) birds and

mammals in the tropical forests of different continents, the slope is found

to be 1.15. What do steeper slopes mean in this context?

15.1.3 The importance of Species Diversity to the Ecosystem

Does the number of species in a community really matter to the functioning

of the ecosystem?This is a question for which ecologists have not been

able to give a definitive answer. For many decades, ecologists believed

that communities with more species, generally, tend to be more stable

than those with less species. What exactly is stability for a biological

community? A stable community should not show too much variation

in productivity from year to year; it must be either resistant or resilient to

occasional disturbances (natural or man-made), and it must also be

resistant to invasions by alien species. We don’t know how these attributes

are linked to species richness in a community, but David Tilman’s

long-term ecosystem experiments using outdoor plots provide some

tentative answers. Tilman found that plots with more species showed

less year-to-year variation in total biomass. He also showed that in his

experiments, increased diversity contributed to higher productivity.

Although, we may not understand completely how species richness

contributes to the well-being of an ecosystem, we know enough to realise

that rich biodiversity is not only essential for ecosystem health but

imperative for the very survival of the human race on this planet. At a

time when we are losing species at an alarming pace, one might ask–

Does it really matter to us if a few species become extinct? Would Western

Ghats ecosystems be less functional if one of its tree frog species is lost

forever? How is our quality of life affected if, say, instead of 20,000 we

have only 15,000 species of ants on earth?

There are no direct answers to such näive questions but we can develop

a proper perspective through an analogy (the ‘rivet popper hypothesis’)

used by Stanford ecologist Paul Ehrlich. In an airplane (ecosystem) all

parts are joined together using thousands of rivets (species). If every

passenger travelling in it starts popping a rivet to take home (causing a

species to become extinct), it may not affect flight safety (proper functioning

of the ecosystem) initially, but as more and more rivets are removed, the

plane becomes dangerously weak over a period of time. Furthermore,

which rivet is removed may also be critical. Loss of rivets on the wings

(key species that drive major ecosystem functions) is obviously a more

serious threat to flight safety than loss of a few rivets on the seats or

windows inside the plane.

15.1.4 Loss of Biodiversity

While it is doubtful if any new species are being added (through speciation)

into the earth’s treasury of species, there is no doubt about their continuing

losses. The biological wealth of our planet has been declining rapidly

and the accusing finger is clearly pointing to human activities. The

colonisation of tropical Pacific Islands by humans is said to have led to

the extinction of more than 2,000 species of native birds. The IUCN Red

List (2004) documents the extinction of 784 species (including 338

vertebrates, 359 invertebrates and 87 plants) in the last 500 years. Some

examples of recent extinctions include the dodo (Mauritius), quagga

(Africa), thylacine (Australia), Steller’s Sea Cow (Russia) and three

subspecies (Bali, Javan, Caspian) of tiger. The last twenty years alone

have witnessed the disappearance of 27 species. Careful analysis of records

shows that extinctions across taxa are not random; some groups like

amphibians appear to be more vulnerable to extinction. Adding to the

grim scenario of extinctions is the fact that more than 15,500 species

world-wide are facing the threat of extinction. Presently, 12 per cent of

all bird species, 23 per cent of all mammal species, 32 per cent of all

amphibian species and 31per cent of all gymnosperm species in the world

face the threat of extinction.

From a study of the history of life on earth through fossil records, we

learn that large-scale loss of species like the one we are currently

witnessing have also happened earlier, even before humans appeared on

the scene. During the long period (> 3 billion years) since the origin and

diversification of life on earth there were five episodes of mass extinction

of species. How is the ‘Sixth Extinction’ presently in progress different

from the previous episodes? The difference is in the rates; the current

species extinction rates are estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times faster

than in the pre-human times and our activities are responsible for the

faster rates. Ecologists warn that if the present trends continue,

nearly half of all the species on earth might be wiped out within the next

100 years.

In general, loss of biodiversity in a region may lead to (a) decline in

plant production, (b) lowered resistance to environmental perturbations

such as drought and (c) increased variability in certain ecosystem processes

such as plant productivity, water use, and pest and disease cycles.

Causes of biodiversity losses: The accelerated rates of species

extinctions that the world is facing now are largely due to human

activities. There are four major causes (‘ The Evil Quartet’ is the sobriquet

used to describe them).

(i) Habitat loss and fragmentation: This is the most important

cause driving animals and plants to extinction. The most dramatic

examples of habitat loss come from tropical rain forests. Once

covering more than 14 per cent of the earth’s land surface, these

rain forests now cover no more than 6 per cent. They are being

destroyed fast. By the time you finish reading this chapter, 1000

more hectares of rain forest would have been lost. The Amazon

rain forest (it is so huge that it is called the ‘lungs of the planet’)

harbouring probably millions of species is being cut and cleared

for cultivating soya beans or for conversion to grasslands for raising

beef cattle. Besides total loss, the degradation of many habitats by

pollution also threatens the survival of many species. When large

habitats are broken up into small fragments due to various human

activities, mammals and birds requiring large territories and certain

animals with migratory habits are badly affected, leading to

population declines.

(ii) Over-exploitation: Humans have always depended on nature for

food and shelter, but when ‘need’ turns to ‘greed’, it leads to

over -exploitation of natural resources. Many species extinctions

in the last 500 years (Steller’s sea cow, passenger pigeon) were due

to overexploitation by humans. Presently many marine fish

populations around the world are over harvested, endangering the

continued existence of some commercially important species.

(iii) Alien species invasions: When alien species are introduced

unintentionally or deliberately for whatever purpose, some of them

turn invasive, and cause decline or extinction of indigenous species.

The Nile perch introduced into Lake Victoria in east Africa led

eventually to the extinction of an ecologically unique assemblage of

more than 200 species of cichlid fish in the lake. You must be

familiar with the environmental damage caused and threat posed

to our native species by invasive weed species like carrot grass

(Parthenium), Lantana and water hyacinth (Eicchornia). The recent

illegal introduction of the African catfish Clarias gariepinus for

aquaculture purposes is posing a threat to the indigenous catfishes

in our rivers.

(iv) Co-extinctions: When a species becomes extinct, the plant and

animal species associated with it in an obligatory way also become

extinct. When a host fish species becomes extinct, its unique

assemblage of parasites also meets the same fate. Another example

is the case of a coevolved plant-pollinator mutualism where

extinction of one invariably leads to the extinction of the other.

15.2 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION

15.2.1 Why Should We Conserve Biodiversity?

There are many reasons, some obvious and others not so obvious, but all

equally important. They can be grouped into three categories: narrowly

utilitarian, broadly utilitarian, and ethical.

The narrowly utilitarian arguments for conserving biodiversity are

obvious; humans derive countless direct economic benefits from nature-

food (cereals, pulses, fruits), firewood, fibre, construction material,

industrial products (tannins, lubricants, dyes, resins, perfumes ) and

products of medicinal importance. More than 25 per cent of the drugs

currently sold in the market worldwide are derived from plants and 25,000

species of plants contribute to the traditional medicines used by native

peoples around the world. Nobody knows how many more medicinally

useful plants there are in tropical rain forests waiting to be explored.

With increasing resources put into ‘bioprospecting’ (exploring molecular,

genetic and species-level diversity for products of economic importance),

nations endowed with rich biodiversity can expect to reap enormous

benefits.

The broadly utilitarian argument says that biodiversity plays a

major role in many ecosystem services that nature provides. The fast

dwindling Amazon forest is estimated to produce, through

photosynthesis, 20 per cent of the total oxygen in the earth’s atmosphere.

Can we put an economic value on this service by nature? You can get

some idea by finding out how much your neighborhood hospital spends

on a cylinder of oxygen. Pollination (without which plants cannot give

us fruits or seeds) is another service, ecosystems provide through

pollinators layer – bees, bumblebees, birds and bats. What will be the

costs of accomplishing pollination without help from natural

pollinators? There are other intangible benefits – that we derive from

nature–the aesthetic pleasures of walking through thick woods, watching

spring flowers in full bloom or waking up to a bulbul’s song in the

morning. Can we put a price tag on such things?

The ethical argument for conserving biodiversity relates to what we

owe to millions of plant, animal and microbe species with whom we share

this planet. Philosophically or spiritually, we need to realise that every

species has an intrinsic value, even if it may not be of current or any

economic value to us. We have a moral duty to care for their well-being

and pass on our biological legacy in good order to future generations.

15.2.2 How do we conserve Biodiversity?

When we conserve and protect the whole ecosystem, its biodiversity at all

levels is protected – we save the entire forest to save the tiger. This approach

is called in situ (on site) conservation. However, when there are situations

where an animal or plant is endangered or threatened (organisms facing

a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future) and needs

urgent measures to save it from extinction, ex situ (off site) conservation

is the desirable approach.

In situ conservation– Faced with the conflict between development and

conservation, many nations find it unrealistic and economically not feasible

to conserve all their biological wealth. Invariably, the number of species

waiting to be saved from extinction far exceeds the conservation resources

available. On a global basis, this problem has been addressed by eminent

conservationists. They identified for maximum protection certain

‘biodiversity hotspots’ regions with very high levels of species richness

and high degree of endemism (that is, species confined to that region

and not found anywhere else). Initially 25 biodiversity hotspots were

identified but subsequently nine more have been added to the list,

bringing the total number of biodiversity hotspots in the world to 34.

These hotspots are also regions of accelerated habitat loss. Three of

these hotspots – Western Ghats and Sri Lanka, Indo-Burma and

Himalaya – cover our country’s exceptionally high biodiversity regions.

Although all the biodiversity hotspots put together cover less than

2 per cent of the earth’s land area, the number of species they collectively

harbour is extremely high and strict protection of these hotspots could

reduce the ongoing mass extinctions by almost 30 per cent.

In India, ecologically unique and biodiversity-rich regions are legally

protected as biosphere reserves, national parks and sanctuaries. India

now has 14 biosphere reserves, 90 national parks and 448 wildlife

sanctuaries. India has also a history of religious and cultural traditions

that emphasised protection of nature. In many cultures, tracts of forest

were set aside, and all the trees and wildlife within were venerated and

given total protection. Such sacred groves are found in Khasi and Jaintia

Hills in Meghalaya, Aravalli Hills of Rajasthan, Western Ghat regions of

Karnataka and Maharashtra and the Sarguja, Chanda and Bastar areas

of Madhya Pradesh. In Meghalaya, the sacred groves are the last refuges

for a large number of rare and threatened plants.

Ex situ Conservation– In this approach, threatened animals and plants

are taken out from their natural habitat and placed in special setting

where they can be protected and given special care. Zoological parks,

botanical gardens and wildlife safari parks serve this purpose. There are

many animals that have become extinct in the wild but continue to be

maintained in zoological parks. In recent years ex situ conservation has

advanced beyond keeping threatened species in enclosures. Now gametes

of threatened species can be preserved in viable and fertile condition for

long periods using cryopreservation techniques, eggs can be fertilised in

vitro, and plants can be propagated using tissue culture methods. Seeds

of different genetic strains of commercially important plants can be kept

for long periods in seed banks.

Biodiversity knows no political boundaries and its conservation is

therefore a collective responsibility of all nations. The historic Convention

on Biological Diversity (‘The Earth Summit’) held in Rio de Janeiro in

1992, called upon all nations to take appropriate measures for

conservation of biodiversity and sustainable utilisation of its benefits. In

a follow-up, the World Summit on Sustainable Development held in 2002

in Johannesburg, South Africa, 190 countries pledged their commitment

to achieve by 2010, a significant reduction in the current rate of biodiversity

loss at global, regional and local levels.

SUMMARY

Since life originated on earth nearly 3.8 billion years ago, there had

been enormous diversification of life forms on earth. Biodiversity refers

to the sum total of diversity that exists at all levels of biological

organisation. Of particular importance is the diversity at genetic, species

and ecosystem levels and conservation efforts are aimed at protecting

diversity at all these levels.

More than 1.5 million species have been recorded in the world, but

there might still be nearly 6 million species on earth waiting to be

discovered and named. Of the named species, > 70 per cent are animals,

of which 70 per cent are insects. The group Fungi has more species

than all the vertebrate species combined. India, with about 45,000

species of plants and twice as many species of animals, is one of the 12

mega diversity countries of the world.

Species diversity on earth is not uniformly distributed but shows

interesting patterns. It is generally highest in the tropics and decreases

towards the poles. Important explanations for the species richness of

the tropics are: Tropics had more evolutionary time; they provide a

relatively constant environment and, they receive more solar energy

which contributes to greater productivity. Species richness is also

function of the area of a region; the species-area relationship is generally

a rectangular hyperbolic function.

It is believed that communities with high diversity tend to be less

variable, more productive and more resistant to biological invasions.

Earth’s fossil history reveals incidence of mass extinctions in the past,

but the present rates of extinction, largely attributed to human activities,

are 100 to 1000 times higher. Nearly 700 species have become extinct

in recent times and more than 15,500 species (of which > 650 are from

India) currently face the threat of extinction. The causes of high

extinction rates at present include habitat (particularly forests) loss

and fragmentation, over -exploitation, biological invasions and

co-extinctions.

Earth’s rich biodiversity is vital for the very survival of mankind.

The reasons for conserving biodiversity are narrowly utilitarian, broadly

utilitarian and ethical. Besides the direct benefits (food, fibre, firewood,

pharmaceuticals, etc.), there are many indirect benefits we receive

through ecosystem services such as pollination, pest control, climate

moderation and flood control. We also have a moral responsibility to

take good care of earth’s biodiversity and pass it on in good order to our

next generation.

Biodiversity conservation may be in situ as well as ex situ. In in situ

conservation, the endangered species are protected in their natural

habitat so that the entire ecosystem is protected. Recently, 34

‘biodiversity hotspots’ in the world have been proposed for intensive

conservation efforts. Of these, three (Western Ghats-Sri Lanka,

Himalaya and Indo-Burma) cover India’s rich biodiversity regions. Our

country’s in situ conservation efforts are reflected in its 14 biosphere

reserves, 90 national parks, > 450 wildlife sanctuaries and many sacred

groves. Ex situ conservation methods include protective maintenance

of threatened species in zoological parks and botanical gardens, in vitro

fertilisation, tissue culture propagation and cryopreservation of

gametes.

EXERCISES

- Name the three important components of biodiversity.

- How do ecologists estimate the total number of species present in the

world?

- Give three hypotheses for explaining why tropics show greatest levels

of species richness. - What is the significance of the slope of regression in a species – area

relationship? - What are the major causes of species losses in a geographical region?

- How is biodiversity important for ecosystem functioning?

- What are sacred groves? What is their role in conservation?

- Among the ecosystem services are control of floods and soil erosion.

How is this achieved by the biotic components of the ecosystem? - The species diversity of plants (22 per cent) is much less than that of

animals (72 per cent). What could be the explanations to how animals

achieved greater diversification? - Can you think of a situation where we deliberately want to make a

species extinct? How would you justify it?

2 responses to “CHAPTER 15 BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION”

hi!,I loke your writing so much! share we be in contact more about your article onn AOL?

I require a specialist in thos space tto resolve my problem.

May be that’s you! Taking a look ahead to per you. https://zeleniymis.com.ua/

hi!,I like your writing so much! share we bee in contact more

about your article on AOL? I require a specialist inn this space to reesolve my problem.

May be that’s you! Taking a look ahead to peer you. https://zeleniymis.com.ua/